Building OpenEngineData

From Reverse-Engineering Binary Files to a Full Aviation Data Platform

The Problem

General aviation pilots who care about their engines invest in engine monitors, a popular choice are the JPI Engine Data Management (EDM) devices. These instruments continuously record critical engine parameters during flight: exhaust gas temperatures (EGT), cylinder head temperatures (CHT), fuel flow, RPM, manifold pressure, oil temperature, and more. For pilots flying piston aircraft, this data is invaluable for detecting problems early and optimizing engine performance.

The challenge? JPI stores this data in a proprietary binary format with no publicly available specification. The official JPI software, EZTrends, only runs on Windows and hasn't been significantly updated in years. Third-party services like SavvyAnalysis exist, but require uploading your data to their servers and subscribing to their service.

The Goal

Create an open-source toolkit that lets pilots analyze their own engine data—locally if they prefer—without vendor lock-in or mandatory subscriptions.

This project evolved through four distinct phases: reverse-engineering the file format, building a Ruby gem, porting to TypeScript for browser use, creating a full web platform, and finally packaging a desktop app. Each phase built on the previous one, and each brought its own technical challenges.

Phase 1: Cracking the Format

The first step was understanding how JPI encodes flight data. Through clean-room analysis—examining real JPI files and cross-referencing with community forum discussions—I pieced together the binary format.

ASCII Headers with XOR Checksums

JPI files begin with an ASCII header containing metadata about the recording device and configuration. Each line ends with a checksum calculated by XORing all characters:

# Simplified checksum validation

def valid_checksum?(line)

data, checksum = line[0..-3], line[-2..-1]

calculated = data.bytes.reduce(0) { |acc, b| acc ^ b }

calculated.to_s(16).upcase.rjust(2, '0') == checksum

endDelta Compression

The real complexity is in the flight data. JPI doesn't store absolute values for each parameter—it uses delta compression. Each record only stores the change from the previous record. A bitmask indicates which fields changed:

# Simplified delta decompression

def decompress_record(bitmask, data_stream, previous_values)

current = previous_values.dup

FIELD_ORDER.each_with_index do |field, index|

if bitmask[index] == 1 # Field changed

delta = read_signed_byte(data_stream)

current[field] += delta

end

end

current

endGPS Coordinate Handling

GPS data added another layer of complexity. Initial coordinates are stored as 32-bit integers with 1/6000 degree resolution. Subsequent positions use 8-bit or 16-bit deltas. And there's a quirk: it appears when the GPS powers on, my Garmin 430 report coordinates in Kansas (the Garmin headquarters location) until lock is reacquired. The parser needs to detect and ignore these "Kansas" values.

# GPS uses special "handshake" values to indicate lock status

HANDSHAKE_VALUE = 100 # ±100 indicates GPS state change

def gps_handshake?(lat_delta, lon_delta)

lat_delta.abs == HANDSHAKE_VALUE || lon_delta.abs == HANDSHAKE_VALUE

endPhase 2: The Ruby Gem

With the format understood, I built jpi_edm_parser—a Ruby gem that handles all the complexity of parsing JPI files.

Architecture

The gem follows a clean object hierarchy:

JpiEdmParser::File # Entry point, handles file I/O

├── HeaderParser # ASCII header parsing, checksum validation

├── Flight # Individual flight with metadata

│ └── FlightRecord # Per-6-second data points

└── IndexEntry # Flight index for multi-flight filesUsage

require 'jpi_edm_parser'

jpi = JpiEdmParser::File.new('path/to/file.jpi')

puts "Tail Number: #{jpi.tail_number}"

puts "EDM Model: #{jpi.model}"

puts "Found #{jpi.flights.count} flights"

jpi.flights.each do |flight|

puts "Flight #{flight.flight_number}: #{flight.date}"

puts " Duration: #{flight.duration_hours} hours"

puts " Records: #{flight.records.count}"

flight.records.each do |record|

puts " EGT1: #{record[:egt1]}°F, CHT1: #{record[:cht1]}°F"

end

endThe gem supports all JPI EDM models (700, 730, 800, 830, 900/930/960 series) and extracts 48+ parameters including EGT, CHT, TIT, oil temperature/pressure, fuel flow, RPM, manifold pressure, and GPS coordinates.

Phase 3: Going Client-Side

The Ruby gem works great for server-side processing, but some pilots are hesitant to upload their flight data to external servers. The solution: port the parser to TypeScript so it can run entirely in the browser.

Privacy First

With the TypeScript parser, pilots can analyze their data without it ever leaving their computer. The browser does all the work locally.

Porting Challenges

Ruby and TypeScript handle binary data very differently. Ruby's String#unpack makes it easy to interpret byte sequences, while TypeScript requires working with DataView and ArrayBuffer:

// TypeScript binary reading

class BinaryReader {

private view: DataView;

private offset: number = 0;

readInt16LE(): number {

const value = this.view.getInt16(this.offset, true);

this.offset += 2;

return value;

}

readSignedByte(): number {

const value = this.view.getInt8(this.offset);

this.offset += 1;

return value;

}

}The core parsing logic—delta decompression, GPS handling, checksum validation—remained identical. The TypeScript version produces the same output as the Ruby gem, ensuring consistency across platforms.

Phase 4: The Web Platform

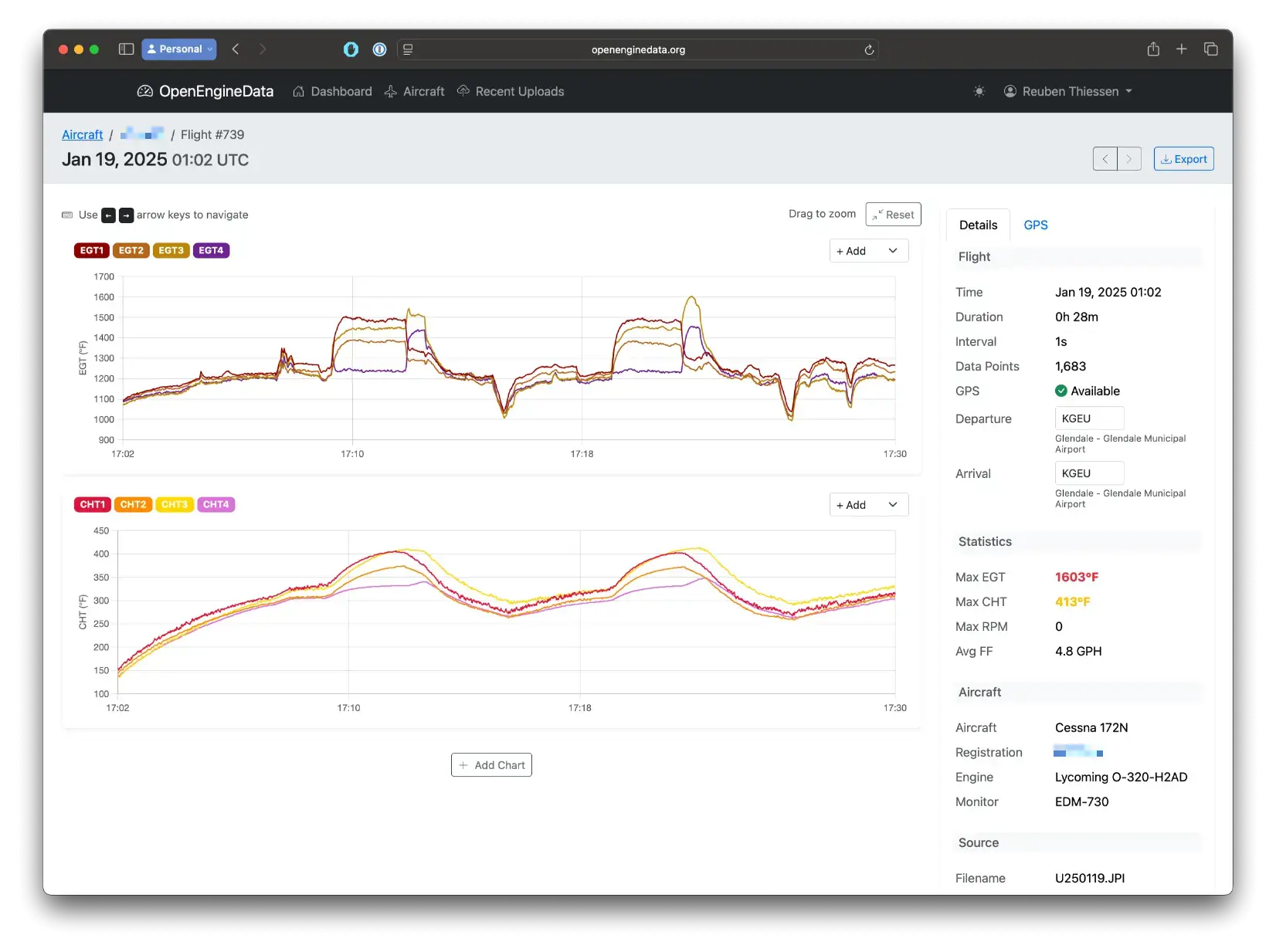

With both server-side (Ruby) and client-side (TypeScript) parsers available, I built OpenEngineData.org—a full-featured web platform for engine data analysis.

Technology Stack

Real-Time Upload Progress

When you upload a JPI file, the browser immediately shows processing status via WebSockets. The navbar shows a spinner during processing, then updates to show how many flights were imported—all without page refreshes.

# Broadcasting upload progress via Action Cable

class ParseFlightJob < ApplicationJob

def perform(aircraft_id, blob_id, upload_id)

upload = Upload.find(upload_id)

upload.update!(status: :processing)

broadcast_status(upload)

# Parse the file...

flights_created = parse_jpi_file(blob_id, aircraft_id)

upload.update!(status: :complete, flight_count: flights_created)

broadcast_status(upload)

end

private

def broadcast_status(upload)

UploadNotificationsChannel.broadcast_to(

upload.user,

{ upload_id: upload.id, status: upload.status }

)

end

endKey Features

- Multi-aircraft management — Track multiple aircraft with photos and engine configurations

- Interactive charts — EGT, CHT with drag-to-zoom and customizable overlays

- GPS track visualization — See your flight path on an interactive map

- Flight sharing — Generate secure links to share flights with mechanics

- CSV export — Download your data in a universal format

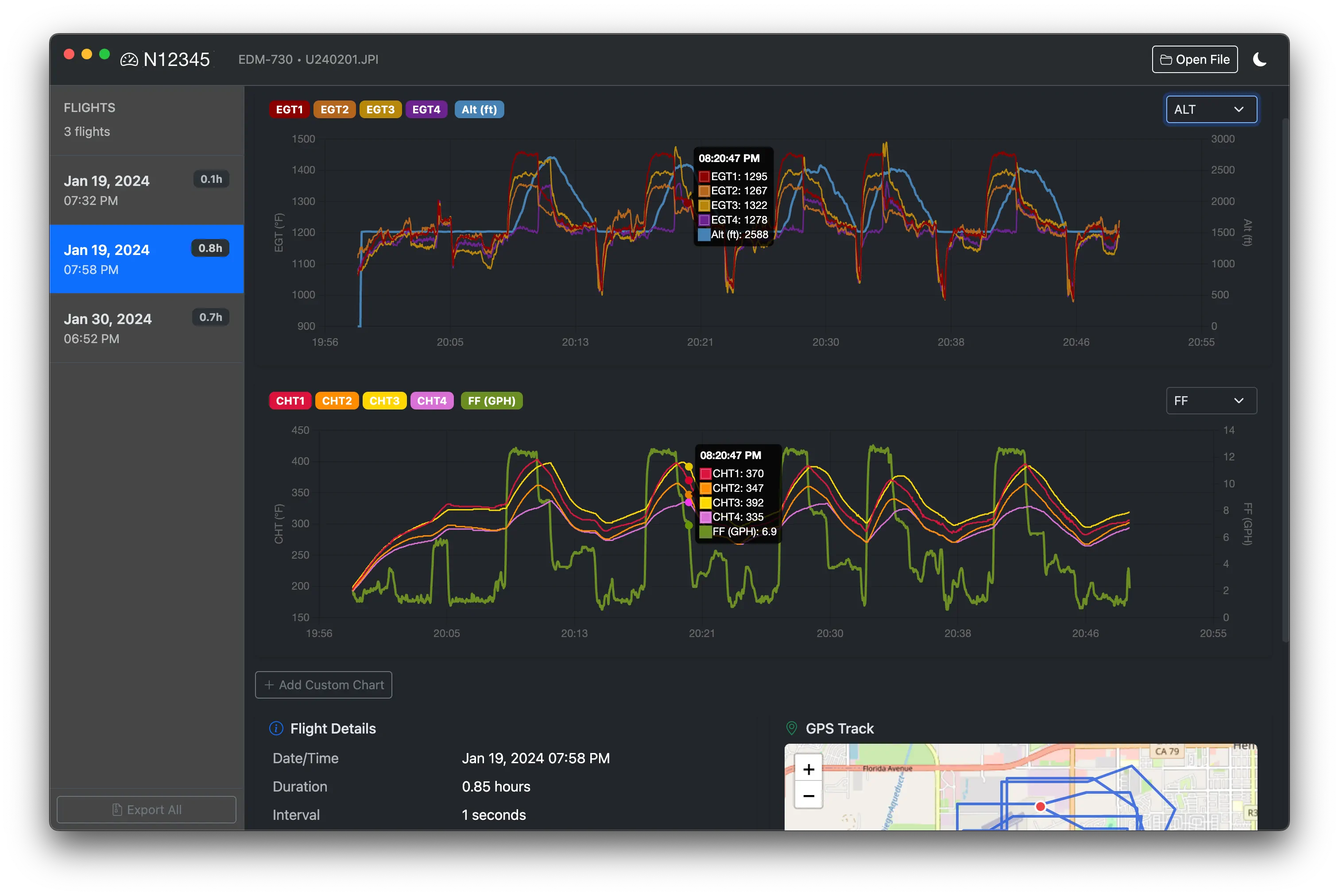

Phase 5: Desktop App

For pilots who want a native app experience—or who don't want to use a web browser at all—I built OED Viewer using Electron.

Cross-Platform Distribution

OED Viewer is built for all major platforms:

- macOS — DMG installer, signed and notarized by Apple

- Windows — NSIS installer and portable executable

- Linux — AppImage and Debian packages

Auto-Updates

Using electron-updater, the app checks for updates automatically on launch. When a new version is available, users see a toast notification and can download and install with one click.

// Auto-update initialization

autoUpdater.autoDownload = false; // Let user choose

autoUpdater.autoInstallOnAppQuit = true;

autoUpdater.on('update-available', (info) => {

sendUpdateStatus(mainWindow, 'available', {

version: info.version,

releaseNotes: info.releaseNotes

});

});

autoUpdater.on('download-progress', (progress) => {

sendUpdateStatus(mainWindow, 'downloading', {

percent: progress.percent,

transferred: progress.transferred,

total: progress.total

});

});Code Signing & Notarization

For macOS, Apple requires apps to be signed and notarized. This involves:

- Signing with a Developer ID certificate

- Submitting to Apple's notarization service

- Stapling the notarization ticket to the app

The build process handles all of this automatically using electron-builder with appropriate entitlements.

Technical Deep Dive: The 0-1 Byte Offset Bug

The Symptom

Some JPI files parsed perfectly. Others would start correctly, then produce garbage data partway through—or miss flights entirely. The pattern seemed random.

The Root Cause

JPI files use word-aligned (2-byte) lengths in their flight index, but actual data can have odd byte counts. When calculating where each flight starts in the file:

# The index entry stores data_words (2-byte units)

# But actual data can have odd byte lengths!

# WRONG: This sometimes misses by 1 byte

position = previous_position + (index_entry.data_words * 2)

# CORRECT: Account for potential padding

actual_data_length = index_entry.data_length # May be odd

position = previous_position + actual_data_length

# But index_entry.data_words * 2 might round up!The Fix

The solution required carefully tracking actual byte positions rather than trusting the word-aligned values from the index. For each flight, we scan forward to find the actual flight header magic bytes, accounting for ±1 byte variance:

def find_flight_at_position(expected_position)

# Search within a small window around expected position

(-1..1).each do |offset|

pos = expected_position + offset

if valid_flight_header_at?(pos)

return pos

end

end

nil

endThis fix had to be carefully ported to both the Ruby and TypeScript implementations, and tested against dozens of real-world JPI files to ensure consistency.

Lessons Learned

Fewer dependencies, fewer problems

Rails 8's Solid Stack eliminated Redis. The TypeScript parser has zero dependencies. Simplicity pays dividends in maintenance.

Port logic carefully

When implementing the same algorithm in multiple languages, test with identical inputs and verify byte-for-byte output consistency.

Build the core once, deploy everywhere

A well-tested parsing library became a Ruby gem, a TypeScript module, a web app backend, and an Electron app—all from the same logic.

Document as you decode

Writing detailed format documentation while reverse engineering saves future debugging. Your notes become the spec that doesn't exist.